naqsh-e jahan square architecture + video

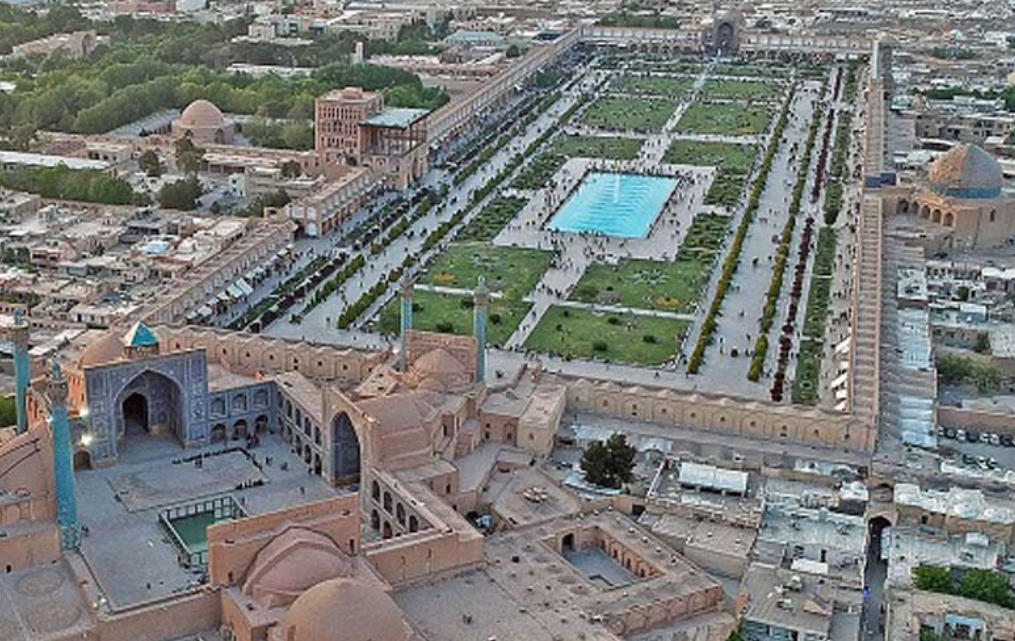

Naqsh-e Jahan Square, known as “Image of the World Square” in English, stands as an embodiment of the pinnacle of Safavid architectural and urban design. Located in the heart of the city of Isfahan, Iran, this square, also referred to as Imam Square, has been a significant hub of commerce, religion, and politics since the early 17th century. Its architectural marvels, spanning from mosques to palaces, illustrate a harmonious blend of Persian and Islamic architectural traditions.

ISFAHAN | Naghshe Jahan Square :

Historical Context

The Naqsh-e Jahan Square was commissioned in 1598 by Shah Abbas I, the 5th Safavid Shah, when he decided to move the capital of his empire from Qazvin to Isfahan. The square was a central piece in his effort to transform Isfahan into a grand capital, befitting the might and splendor of the Safavid dynasty. This transformation was not only a reflection of the dynasty’s earthly power but also mirrored their spiritual aspirations.

Layout and Design

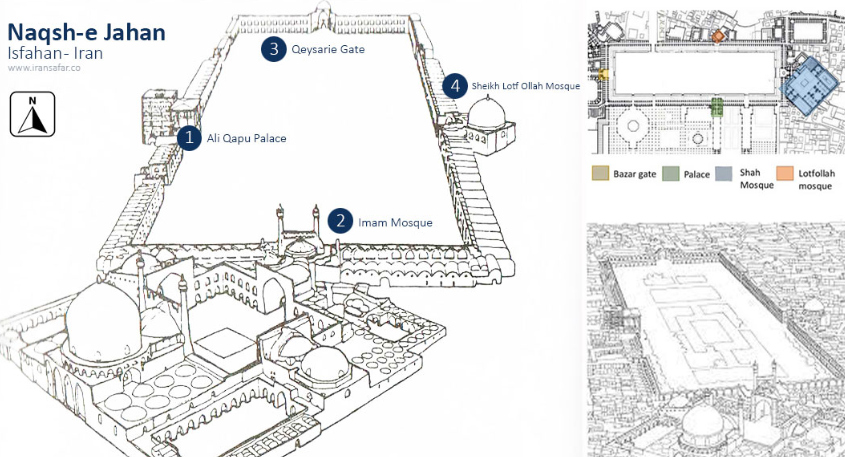

The square, a UNESCO World Heritage site since 1979, is one of the world’s largest city squares, spanning approximately 560 meters by 160 meters. Laid out as a rectangle, its long axis aligns with the cardinal directions, demonstrating the Persian love for symmetrical and axial planning. The four sides of the square house architectural masterpieces: the Shah Mosque in the south, the Sheikh Lotfollah Mosque on the east, the Ali Qapu Palace on the west, and the entrance to the Grand Bazaar in the north.

Architectural Marvels

- Shah Mosque (Imam Mosque): This mosque is a defining example of Safavid architecture with its magnificent entrance portal, adorned with intricate tile work in blue and gold. The dome, standing at about 53 meters in height, is a marvel in its design, showcasing the acoustics and construction capabilities of the period. The interiors glow with an array of mosaics, calligraphic inscriptions, and haft rangi tiles. These tiles demonstrate a seven-color palette, which was a significant innovation during the Safavid period.

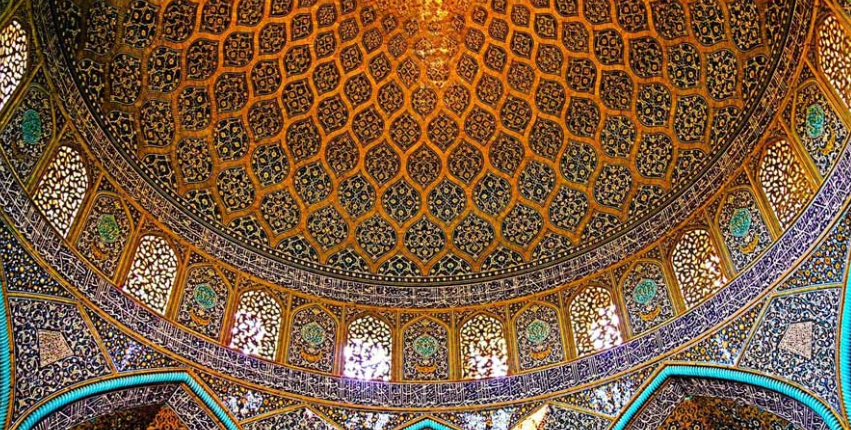

- Sheikh Lotfollah Mosque: Unlike the Shah Mosque, this mosque was primarily meant for the royal family, evident in its more intimate scale and lack of minarets. Its dome, displaying a peacock at its zenith under certain lighting conditions, is a marvel of mosaic tilework. The entrance is slightly angled to face Mecca, and the interiors are replete with mesmerizing patterns and hues.

- Ali Qapu Palace: Serving as the royal palace, Ali Qapu is a six-story building providing a panoramic view of the square. It’s celebrated for its music hall, where deep niches in the walls were constructed to enhance acoustics. These niches, apart from their acoustic purposes, form aesthetic patterns, revealing the harmonious blend of form and function.

- Grand Bazaar (Qeysarie Gate): The northern side leads to the bustling Grand Bazaar, a labyrinthine market selling everything from spices to Persian rugs. The entrance, marked by the Qeysarie Gate, is adorned with a beautiful clock, a reminder of the importance of commerce in the Safavid era.

Artistry and Craftsmanship

One cannot discuss Naqsh-e Jahan Square’s architecture without acknowledging the unparalleled craftsmanship. The tilework, spanning various hues, patterns, and techniques, is a visual feast. These tiles were not just decorative elements; they often narrated stories, displayed astrological symbols, or reflected theological beliefs. The stucco work and muqarnas (stalactite-like structures hanging from arches) found in the mosques and palaces are masterclasses in geometry and design.

Influence on Urban Development

The Naqsh-e Jahan Square’s design has influenced urban planning well beyond the confines of Isfahan. The square acted as a template, showcasing how multifunctional urban spaces could be harmoniously integrated. It demonstrated the blending of socio-economic activities (like commerce in the bazaar) with spiritual (the mosques) and political (the palace) functions.

In addition, the square provided a model for city expansion. Isfahan grew around the square, with the city’s main thoroughfares radiating outwards, reminiscent of the rays of the sun. This not only made the city easy to navigate but also cemented the square’s importance as the heart of Isfahan.

In Conclusion

The Naqsh-e Jahan Square’s architecture is a testimony to the synthesis of grand vision, architectural innovation, and meticulous craftsmanship. Each structure, from the awe-inspiring Shah Mosque to the intricate corridors of the Grand Bazaar, tells a story of the Safavid dynasty’s ambitions and achievements. This square stands as an enduring symbol of Persian and Islamic architectural prowess and remains an inspiration to urban designers and architects worldwide.